Anne Sexton

“Live or die, but don’t poison everything”:

Wellesley’s Anne Sexton (WHS 1947)

by Beth Hinchliffe

I was sitting at my desk in my Wellesley College dorm when the phone rang. I was exhilarated because I was transcribing the interview I’d just had with poet Anne Sexton—she was a kind of goddess to English majors, and I had been thrilled when she granted my shy request to meet.

It was my mother calling, to tell me that Anne had just killed herself.

I turned off the tape recorder, but could still hear her voice echoing in the room. I searched through my notes for clues. Yes, at one point she had said, “I’m not dead. Not yet,” but after spending the afternoon with her I had come away dazzled by the sensation that she was not just filled with life, but larger than life.

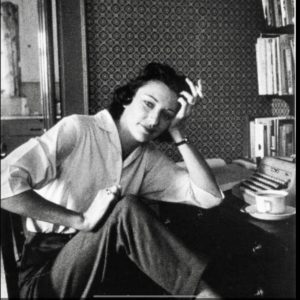

We’d met in the cluttered, dark, wood-paneled study of her longtime home at 14 Black Oak Road in Weston, just off her sunny kitchen with incongruously cheerful gingerbread men on the curtains. She ionized the room. In my memory everything else was black and white (ironically, especially her Dalmatians), whereas she exploded through in drenched technicolor.

Her voice was three notches louder and three notches deeper than average, hoarse and whisky-edged. Her gestures suited a stage, not a cramped room. She was never still, moving with the natural yet calculated sensuality of the model she had been, continually entwining her legs while her equally graceful yet silent dogs mirrored her.

At 45, her Jane Russell face never looked the same from one moment to the next, emotions flowing and changing in such vivid succession that I always felt a step behind.

In her large hands, with her long, unpolished, ink-splattered fingers, she held a succession of cigarettes, smoking in the same concentrated way she talked, inhaling so deeply that her cheeks hollowed, holding in the smoke as if desperate to drain every molecule, exhaling in a noisy cloud that obscured her face.

But, of course, it was her words that riveted, their intensity that exhausted. One of the most famous poets in the country, she had received almost every award possible, from the Pulitzer Prize to Ford and Guggenheim and the American Academy of Arts and Letters Fellowships. She, along with Robert Lowell and Sylvia Plath, had created and embodied the “confessional” school of poetry, writing fiercely and uncompromisingly about their mental illnesses, hospitalizations, and suicide attempts. And she spoke as she wrote, with words that were harsh, stark, and unflinching.

“I am not depressed,” she said suddenly, in regard to nothing we had been discussing. “I am in despair.” Those are the words that summed up the tone of our talk. “Life, for me, is despair.”

She spoke of her Wellesley childhood, her current Weston life. “My poetry shocks my neighbors,” she said. “It’s raw and cruel. They say it’s not me. But it’s the true me.”

She talked of the girl she’d been growing up in Wellesley (at 81 Garden Road, just a short walk to the Brown School and the Wellesley Hills Congregational Church where she went to Sunday School), who belonged more to a world of fairy tales and fears than playgrounds. (A third generation Wellesley child, her grandfather had been president of the Wellesley National Bank.)

Looking back at her years in Wellesley, she dismissed her teenage self as a “pimply, boy-crazy thing” who was obsessed with flirting and received a “C” in her 10th grade American Literature class (with an “F” for effort). (She did not graduate with her Class of 1947 from WHS, going instead to boarding school.)

Eloping at 19, she worked for a while as a clerk at Hathaway House Bookshop (the yellow once-farmhouse that now houses offices, at the corner of Weston Road and Central Street in Wellesley Square), but it wasn’t until she’d had two children, a suicide attempt, and a lengthy psychiatric hospitalization, that she “found [her] essence” when she began to write poetry at 27.

Anne and Sylvia Plath overlapped as children in Wellesley, but never knew each other until they met in 1959 as adults auditing Robert Lowell’s poetry seminar at Boston University. It was a legendary, combustible combination. “We were suicide-sisters, draining each other of every detail of our attempts,” Anne said of the intense bond they formed. “We lusted after it.”

Four short years later, years filled with publications and honors for each of them as they suddenly exploded into the international literary world, Sylvia killed herself. As soon as she heard the news, Anne wrote a furious poem fueled by grief and envy called “Sylvia’s Death:” “Thief —how did you crawl into,/crawl down alone/into the death I wanted so badly and for so long.”

“My time will come,” Anne said to me. “Sylvia had the suicide inside her. So do I.”

Yet she also talked of things that seemingly tethered her to life: her daughters, near my age, off at school; her many poetry readings, some set to the music of her own jazz group; the beauty of the swamp maples that encircled her home; her puckish delight at the enormous boulder that seemed to rise up out of the earth in the front yard, “a totem, protecting me;” an honorary degree which would have impressed her father; her recently published volume The Death Notebooks; and new poems which would be published posthumously as The Awful Rowing Toward God.

When we parted, she gave me a signed copy of an unpublished poem she had just finished called “The Sickness Unto Death”, and graciously, warmly asked to see copies of my writings.

And then, a blink of an eye later, on that brilliant fall day, in her running car in her closed garage, Anne followed Sylvia into “the sweet death we both yearned for.”

(Reprinted from WellesleyWeston Magazine)